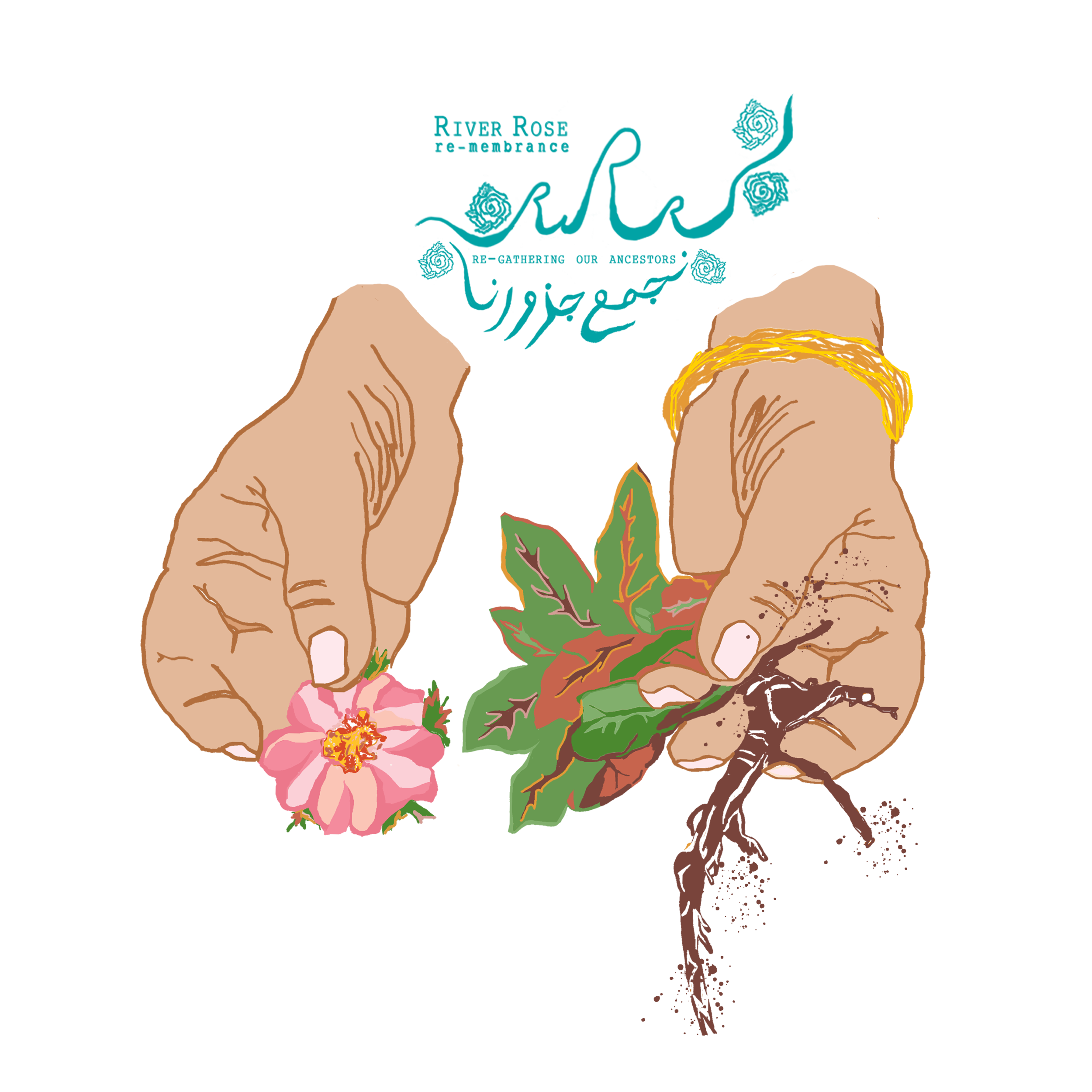

The Life of Flowers: An Interview with Artivist Paradise Khanmalek

Interview by Tala Khanmalek

LA-based artivist Paradise Khanmalek is gearing up to publish her first ever children’s book, The Life of Flowers. In the interview below, Paradise and I chat about why she chose to focus on plants that are native to her homeland, Iran. For more information about Paradise, or to purchase her work, check out: Pardislili.com, Paom.com/stores/rose-water and, Society6.com/paradise420.

Tala Khanmalek:

Is The Life of Flowers your first children's book? How did this project emerge?

Paradise Khanmalek:

The Life of Flowers is my first children's coloring book. I had made an illustrated book of poetry called Reality, which can be purchased here, for the LA Zine Fest. My mother bought a copy and took it to her home and shared it with her then roommate who just happened to be a translator/publisher for American books in Iran. She liked my work and approached me about creating a children's book. I thought about what kind of children's book I'd be interested in putting together and decided on a coloring book about plants and nature. I want children to learn about photosynthesis, the importance and magic of plant life, and where their favorite flowers and herbs come from before they're on a dinner plate or table. I also was thinking about what I enjoy drawing. When I'm free drawing on my own time, I naturally feel inclined to draw eyes, moons, and plants; things with sweeping curves and shapes. So the choice to make this book about plants was also about my own visceral enjoyment and experience. I hope that translates to my viewers.

TK:

Why did you choose to create a book about plants? Why is it important for children to learn about their plantcestors?

PK:

I feel like nature, gardening, and traditional farming practices are a huge part of the climate change conversation that gets looked over in exchange for promises of technological advancement and "clean" industrial practices. That’s all fine and good but I want people to remember that we already know how to live in symbiosis with nature, or at least we know a lot. Our grandmas know a lot. In addition to talking about solar power and engineering development in machinery that effect our climate, we should also bear in mind how to take better care of our forests, encourage urban farming, and shifting from the harmful, environmentally ludicrous practices of industrial farming to organic and bio dynamic farming.

mint

I feel like as a child, I had a very disjointed connection with what I was eating, where it was grown, and how it got to me. A part of the environmental impact conversation has to be FOOD and how companies like Monsanto are essentially slowly poisoning primarily working class people of color. Especially women.

Anyways, this is all to say that If children learn where their food comes from, how their favorite flowers blossom in the wild, and how plants exist with sun, water, and soil, maybe they'll connect that systemic loop of farm-store-table early in life and form a more whole vision of eating. However, this is based on my experience of food and life in the U.S, and this book is first being published in Iran. I do want to publish it in the U.S in the future but I don't have a publisher for that yet. As this book exists in Iran, I particularly chose plants native to Iran so that children can connect what they learn to plants they see at the dinner table or on the New Year Haft Sin altar. I also grew up with these plants in my home so it was a rich learning experience for me as well to research how and where these plants grow best.

TK:

Not only are the plants in your book native to Iran, their facial expressions are distinctly SWANA! Can you share a little bit about why you gave the plants faces and why you drew them like this?

PK:

I originally didn't have faces on the plants but my publisher encouraged me to make them characters. It was a great suggestion because I had a lot of fun with that. I always draw faces in this Iranian miniature inspired style. When I was a child, I consistently and exclusively drew white people, figures with blond hair, blue eyes, and pointed button noses. When I was 19 and blossoming into my racial consciousness, I realized how gross and self-hating that was and I started drawing figures that look like me and my family members. Since then, I pretty much exclusively draw faces like my own; curved noses, unibrows, the works. It wasn't even a conscious decision when I started drawing faces like that on the plants, its completely natural to me now.

sunflower

TK:

What’s your relationship to some of these particular plants?

PK:

I love plants, pretty much all plants. They are incredible and a huge inspiration in my art. The particular plants I chose are ones that are present in Iranian culture. Hyacinth/Sonbol is a flower we place in the Haft Sin to symbolize Spring and life. Mint/Nana is an herb we regularly eat fresh and dried as a spice. Jasmine/Yasaman is an Iranian favorite for gardens and parks as well as a common name. Rose is the national flower of Iran, a garden favorite, as well as a flower used in food as rose water. Sun Flowers are actually native to North America but my family loves to eat sunflower seeds/tokhme and I personally love sunflowers. I grew up with these plants as staples in my diet and environment. It was valuable for me to learn about how they exist in nature in creating this book and sharing that.

TK:

How do you understand the connection between plants, culture, and ancestry?

PK:

That's such a complex question. The first thing that comes to mind is the scent of cardamom. Sometimes I make big pots of herb tea using dried rose petals and borage petals. I like to drop two or three whole cardamom pods in the boiling water. The aroma that circles the kitchen when I make this tea is so deeply familial. I feel like I'm hanging out with ancient ghost relatives when I drink it. I feel like plants can almost trigger ancestral memories or sensations. This is probably a very unique experience from diaspora.

hyacinth

In general though, plant life is hugely cultural in that right now, wealthy communities are dominating the economic demand for formerly exclusively indigenous and non-western foods. It's a strange food consumption and distribution gentrification that creates limited access to the communities originally using the food. However, I love the global movements by communities of color to reclaim pre-colonial grains, herbs, and plants. In Iran as well, this is pertinent.

Over my last visit, my mother and I went to an Attari/apothocary. It was a fascinating little store for me because I saw all these herbs that my mother hoards in her cabinets in its original context, the context in which my ancestors interacted with medicinal herbs generations ago. My mother said these attaris are making a come back in that they weren't popular throughout her youth in Tehran. Perhaps In Iran too, a growing respect for traditional relationships to plants is blossoming. I know for sure that it’s blossoming in me. In my own personal experience, I find it incredibly healing to learn the science and contemporary medical thoughts on plants, health, and our bodies a long side the traditional beliefs of my culture and other cultures around food, plant life, gardening, and health.