The Dark Mirror: Reflections on Ancestral Identity through Dreams, Stones, and Mystical Practice

by Kirra Swenerton

“Beauty is life when life unveils her holy face. But you are life and you are the veil. Beauty is eternity gazing at itself in a mirror. But you are eternity and you are the mirror.”

–Kahlil Gibran, The Prophet

I was between 10 and 11 years old when my body begun to transform and I started bleeding every month. I yearned to become a teenager and do teenage things like wear makeup, but I was in the 5th grade and lipstick was a distant fantasy. In spite of this, I managed to acquire one of those round cosmetic mirrors that plugged in and had its own fluorescent light. The mirror must have been right next to my bed because when I burst out of dream that fateful night, I don’t remember getting up or anything at all about my dream. What I do remember, what has stayed with me all these years, is the moment I flipped on the light and in that state of half-waking looked at my own reflection. I saw something in that mirror. I saw someone gazing back at me. Her eyes were just like mine but she was ancient and withered like Grandma Roupen, my Armenian great-grandmother who had died some years before. But it wasn’t Mariam Roupenian’s face either; it was someone else’s. Maybe it was mine?

Photo: Four generations, circa 1977. Clockwise from the bottom left: great-grandmother, Mariam Roupenian; grandmother, Helene Swenerton; mother, Maylien Swenerton; grandmother, Ernestine Ardito; great-grandmother, Edna Sumner; and me, Kirra Swenerton.

Image description: A colour photo with six women from four generations. In the background, three middle-aged women are standing, all wearing collared shirts. In the front, two elderly women, both wearing glasses and collared dresses, are sitting on chairs and holding a baby girl in a red dress and white tights between their laps.

Photo: Helene Swenerton

Image description: Black and white headshot photograph of a woman in her 50’s, smiling and looking confidently into the camera. Her dark hair is pulled back into a loose bun with some strands of grey hair visible around her face. She is wearing small earrings, a chain necklace and a black turtleneck with a patterned vest.

Nearly 30 years passed before I found a way to speak of that night. At the time, I was frightened and couldn’t make sense of what had happened. I hid the memory away in some interior place reserved for things my worldview couldn’t hold. Even at the age of 10, I’d learned to rationalize and minimize my mystical experiences. My own grandmother, Helene, was the queen of objective materialism. The daughter of genocide survivors, my grandmother was a testament to the resilence of our ancestors and fought hard to assimilate into mainstream American culture. After marrying my Anglo-American grandfather and raising three sons, she went back to college, earned her PhD and built a successful career as a research scientist. I never told her about the mirror.

Growing up, I learned very little about Armenian culture. The genocide of the early 1900’s and subsequent loss of homeland left this enormous void that seemed to eclipse all the history that came before it. Everyone who didn’t escape was dead and no one in my family wanted to tell those stories. The survivors intended to move on and they did. Both my grandmother and her older sister, Jeanette, married European Americans as did their children.

Through college and my 20’s I struggled to connect with my Armenian heritage in ways that weren’t explicitly religious, genocide-focused or centered on politics and border disputes. Except for the nose, I present as white and I never learned to speak our language. Still, people would ask me that insidious question: Where are you from? My answer never felt satisfactory. American? Italian? Armenian? British? European? Middle Eastern? All of the above? I knew that behind that question hid the implication that I didn’t belong. I was grasping at ghosts. I didn’t know how to embody the complexity of my ancestry and felt like a fraud claiming heritage that time and distance had nearly erased. Throughout my 30’s, even after years performing in aCentral Asian folkloric dance company, I secretly carried the burden of feeling not Armenian enough, a lingering sense of being an outsider even among other descendants of the diaspora.

I now recognize this desolation and disconnection as a symptom of inherited trauma, shared by many folks within the SWANA community and beyond. This hunger for belonging became the very fuel I needed to persevere in my search for reconnection. All the while, from the other side of the mirror, my ancestors were longing for me to return. I needed to begin with my own body and with the earth beneath my feet. I live, work, sleep and dream on the ancestral homeland of the Ohlone peoples. So when I stumbled across a message from Ohlone artist, Catherine Herrera, stating that the proper way for settlers to do ceremony on this land is to first introduce our ancestors to the ancestors of this land, I felt the pull of my own people calling me to face them.

By the age of 41, I had become an accomplished scientist in my own right, and my grandmother, Helene, had died. In the time leading up to her death, I pursued my longing for personal ancestral healing and had begun training to be a practitioner in that field. I finally had a solid structure for working with my blood lineage ancestors and practiced calling upon them during ritual and in dreams. One day, I was lying beneath an old oak tree in Amah Mutsun territory, where I had been invited to participate in a plant medicine ceremony. The effects of the brew were flowing through me and inside my intricate, animated visions I noticed an orange-flecked shape cutting through the harmony. It seemed like a small, sharp blade cruising along the very edge of my sight. I tried to correct it, to fix it, to heal whatever it was but the little dagger kept coming back into view. It insisted on my attention.

Over the decades since my first blood, my worldview has blown wide open and I’ve learned to accept the gifts and teachings of my mystical experiences. I’ve had opportunities and resources for spiritual growth that my grandparents never did. But with these gifts comes responsibility. So I asked myself, what was the teaching of this dagger? As I sat with all I’d received during the ceremony, I had the strong sensation it was associated with my Armenian grandmothers. The blade itself seemed to be made of a dappled orange and black stone, like mahogany obsidian, and the shape was jagged and hand-hewn. With the momentum of my ancestors behind me, I began searching for images of stone daggers, looking for something that reflected my vision. This line of inquiry led me to an enormous body of geological and archeological research documenting volcanic sites and obsidian stone tools throughout ancient Armenia! I never knew there was obsidian in Armenia, but I was certain I was on the right track.

Photo: Neolithic-style knapped obsidian blades crafted by contemporary Armenian artist, Armen Harutyunyan. Photo by @armold99.

Image description: Screenshot of an Instagram post. The image depicts six obsidian knives with triangular blades, sharp black tips and bone handles affixed with wrapped sinew.

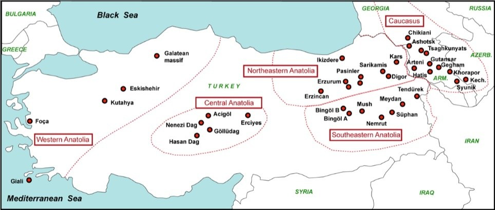

As I followed the trail, I learned that obsidian is a kind of volcanic glass, created when lava cools too rapidly for crystals to form. This can happen when molten lava from a volcano suddenly comes into contact with cold water, as it did around Lake Sevan. I discovered that nearly all of the obsidian used to craft stone tools in the SWANA region, from the Paleolithic era onward, originated from volcanoes in Central and Eastern Anatolia including Cappadocia, Gollu Dag, Nenezi Dag and Nemrut Dag.Anatolian sources of obsidian are known to have been used in the Levant and the Armenian Highlands from as long ago as 12,500 BCE. The oldest traces of obsidian use along the Mediterranean rim have been dated to the Upper Paleolithic period, and are found in caves on the southwest coast of Anatolia. Ancientobsidian artifacts traceable to these sources have been found throughout the SWANA region, indicating that distant communities separated by hundreds of miles and often by mountains and seas have been connected and in communication with one another for an extremely long time.

Map: Obsidian source locations from Obsidatabase.

Image description: Simple map of modern day Turkey, Syria, Iraq, Iran, and surrounding countries, with modern borders in black and pre-colonial borders separating Western, Central, Northeastern and Southeastern Anatolia in red. Village names within these borders are marked, depicting sources of obsidian.

I felt my whole self engaged in this spirit-driven research. There was plenty of room for both the scientist and the dreamer. I dove down the rabbit hole with obsidian, and eventually, in December of 2018, I located a woman in Yerevan willing to send me a chunk of glistening black glass from the birthplace of my grandmother’s people.

That same week in December, seemingly on a whim, I decided to visit theRosicrucian Egyptian Museum in San Jose, California. Amongst all the stunning artifacts housed in the museum, the piece that beckoned to me was a polished bronze mirror, however dubiously it was obtained. I felt the pull from that invisible force, and followed my curiosity into exploring the history of mirrors. What I learned next is still reverberating through my life: the oldest mirrors made by human beings were highly polished obsidian spheres, recovered from an 8,000 year old burial site in Catalhöyük, Anatolia.

Photo: Banu Aydınoğlugil looking at her reflection in an 8,000 year old obsidian mirror from Anatolia. Photo by Jason Quinlan of the Çatalhöyük Research Project.

Image description: A young woman’s hands holding a round, palm-sized stone with both her hands. The stone is an ancient obsidian mirror with a highly polished surface and some scratches. Between the scratches, the young woman’s face who is holding the mirror is reflected with a light blue sky visible behind her.

Some people theorize these ancient, obsidian mirrors were used in early telescopes tomake astronomical observations and gaze up at the moon, planets and stars. Some suspect they were tools for focusing perception, encouraging introspection, contemplation and insight. Others believe these dark reflectors to be tools of the second sight for purposes of divination, scrying and foretelling.

My ancestors lead me back to this knowledge, down a strange and winding path. They’ve been urging me in this direction since I was 10 years old and afraid of my own dreams. They’ve been conspiring with the ancestors of the land where I live and working through the medicine of plants and stones to bring me closer to them. And they are guiding me to rediscover the old practices, ancient tools and technologies long forgotten. They are teaching me that it is possible to reach back through the void of loss and trauma, through time and space and recover some of the magic of this holy earth. They are teaching me to see myself and my place within the mystery. And perhaps, with some practice, I will learn to gaze into the dark mirror, through the portal and into the shadow world where my ancestors and I coexist in a single reflection.

References:

Armen Harutyunyan, Stone Age Knives and Tools https://www.instagram.com/armold99/

Ancestral Medicine https://ancestralmedicine.org/

Ballet Afsaneh http://www.dancesilkroad.org/

Çatalhöyük Research Project http://www.catalhoyuk.com

Düring, B., & Gratuze, B. (2013). Obsidian Exchange Networks in Prehistoric Anatolia: New Data from the Black Sea Region. Paléorient,39(2), 173-182. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309453752

Herrera, Catherine http://www.catherineherrera.com/SweetArtNews/

Indian Canyon https://indiancanyonlife.org/

Obsidatabase, Database on Prehistoric Near East Obsidian https://www.mom.fr/obsidienne/

Rosicrucian Egyptian Museum https://egyptianmuseum.org/

Vit, J., & Rappenglück, M.A. (2016). Looking Through a Telescope with an Obsidian Mirror. Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry, 16(4), 7-15. http://maajournal.com/Issues/2016/Vol16-4/Full2.pdf

Kirra Swenerton is ancestral healing practitioner, restoration ecologist and ritualist. She is the founder of Root Wisdom, offering nature journeys, environmental consulting, psychedelic integration and ceremonial services. Learn more about her work atrootwisdom.com and follow her instagram@rootwisdomcenter.Kirra’s ancestors came from the British Isles and Ireland, the mountains of Northern Italy and the Armenian Highlands. She lives and works on Ohlone land in Oakland, California.